Healthy, But Where is the Joy?

Food as a ritual rather than anxiety

It is a warm summer day in Bulgaria, my grandmother has prepared moussaka for our family: potatoes, vegetables, meat, oil, and creamy yogurt on top. A confluence of local, seasonal ingredients, culinary skill, and a recipe that, by this time, amounts to a family treasure. There are no questions from those around the table: no scrutiny of the ingredients; no angst over whether it was cardio-protective or ketogenic; no one asks if it is gluten-free.

On days like these, food anxiety seems like a contradiction in terms.

We didn’t grow up analyzing food; we embraced it. The only dietary restrictions were out-of-season ingredients; the only rules were the handwritten recipes we had inherited. Our tomatoes in summer dripped with soil and juice. My grandfather kept a garden with a cherry tree, and we never washed the fruit before tasting it. We didn’t eat with the intention of controlling our bodies. We couldn’t wait for the moment when we could sit at a table with those we loved and taste the passage of time.

Years later, when I moved to Italy, I encountered a different kind of reverence. Pasta wasn’t always buried under heavy sauces; it breathed. Aglio, olio, peperoncino, garlic, olive oil, and peppers. In Austria, where I studied in Vienna, food still retains a structure rooted in a history where its people survived on meat and butter. Food was a given, not sanctified. Certainly not feared.

Then came California.

Suddenly, the authenticity I once thought of as a good available to all, was a privilege afforded to a few. A carefully branded premium, locked behind price tags and wellness labels. “Food”, with all its comforts and pleasures, was out, “nutrition” was in, trailing behind its advice and warnings, disclaimers and recommendations.

In a supermarket aisle, I paused in front of a carton of almond milk. I hadn’t tasted dairy in weeks. In the U.S., I discovered that I was lactose intolerant. For the first time, I felt I needed to go through hurdles before any ingredient made it to the shopping cart; food meant tests were expected to be passed, and failure meant abstinence.

There is a kind of violence in putting our bodies through constant micro-testing. Not the kind that screams, but the kind that creeps. That whispers: You must optimize and purify. You must transcend the sin of pleasure.

And yet, somewhere in my bones, a hunger stirred. Not for perfection, but for something older. Something known in the blood of my ancestors.

In Greece, my husband and I eat grilled fish by the water. We dip white bread into olive oil, still green from the press. We sip ouzo without occasion. The breeze carries oregano, and the sea glistens like a God’s eye.

Greeks like to dance, so many of our waiters would sing to us, and tell us stories, pulling us from our chairs to twirl under the stars. Most of the tavernas were inherited: Family-run, woven into the village like the olive trees surrounding them. Tradition wasn’t a performance; it was the water they swam in.

Still, the more American I felt, the harder it became to renounce the labels I’d internalized.

In the U.S., PCOS (Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome) now affects up to 13 percent of women of reproductive age. In Bulgaria, the condition was once so rare it felt almost fictional. Now, even there, it grows. As does gluten intolerance, lactose intolerance, and the litany of no’s we memorize before entering a kitchen.

While to a limited extent these prohibitions are founded on legitimate medical conditions, their accelerating expansion and the traction they’ve gained with society at large represent a larger, more insidious cultural shift.

Michel Foucault described, “an explosion of numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugation of bodies and the control of populations.” He characterised this phenomenon as the onset of biopower. The body becomes supervised “through an entire series of interventions and regulatory controls: a biopolitics of the population”.

The advice, warnings, quantification of nutritional value, and disclaimers that pervade food labels are not neutral expressions of fact. They constitute specific technologies of power, regulating our relationship to our food under the guise of wellbeing. Those institutions created the contaminated food we are subjected to today. First, make the disease, then create the cure.

In this context, the anxiety we feel in the aisles of a supermarket doesn’t reflect a justifiable fear of bread or milk. It is an instinctive rejection of the power that is subtly being exercised over our choices. The fragmentation through the unknown ingredients. The loss of trust. The abstraction of food from the community we were meant to enjoy it with. Something as elementary as real food became complicated, increasingly challenging to obtain.

I often ask myself: When did food become a trend to categorize? Were we not watching closely before, or has the trend metastasized - moved from ingredients to identity? We don’t just eat differently. We brand our eating. “Vegan,” “keto,” “anti-inflammatory,” now, even “intuitive eating.” Do we have to label it intuitive? The words crowd the packaging, but that sense of health we might briefly feel from eating the “right” food doesn’t nourish our souls, as around 25% of Americans now dine alone.

This self-imposed dietary surveillance doesn’t just constrain what we eat; it imposes a moral architecture on eating itself. The “clean” eater is the hyper-conscious consumer. Food choices are governed by what is optimal for them alone. Meanwhile, those who still eat spontaneously and without scrutiny, or still find value in the communality of a shared table, are viewed as relics of a cruder, less sophisticated time.

But food is not merely a tool to render our performance more optimal. It’s a ritualistic inheritance.

I miss the ignorance. There’s something holy about ignorance when it comes to food. The kind that trusted your grandmother’s hands more than the Instagram of a wellness influencer. They believed cabbage rolled around rice and meat was enough, and the more you ate, the better you felt. That didn’t question whether a cake would shorten your life, because you were too busy living it.

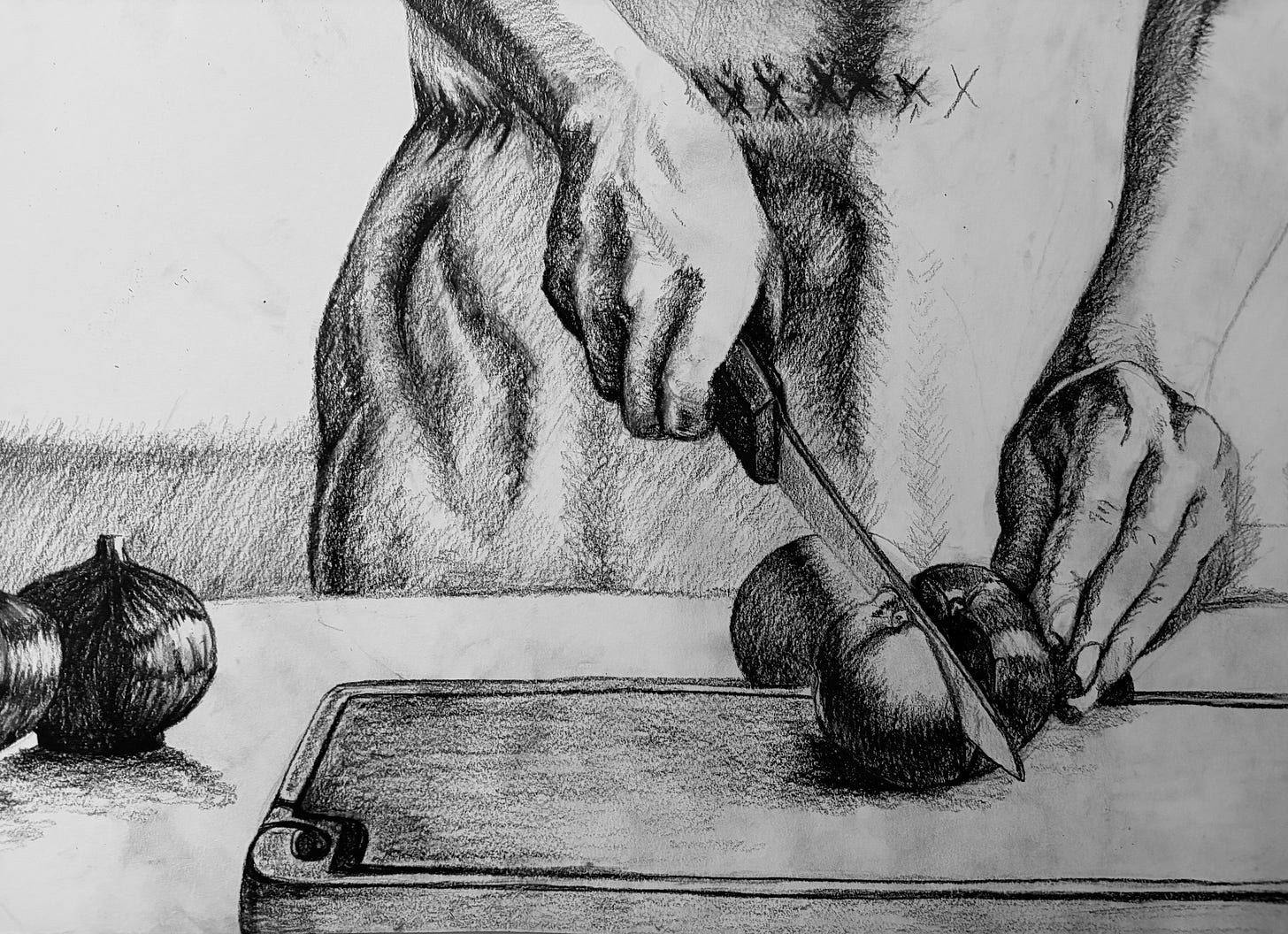

The joy was in repetition. In slicing tomatoes every summer the same way your mother did. In kneading dough by feel, not by measurement. In knowing that a certain salad shows up on the table when the plants ripen, and not a week sooner. That kind of eating doesn’t just nourish the body, it ties you to time, to climate, to seasons, to your people. It makes you a natural element of your environment.

California bears its gifts. Farmers’ markets are ripe with fruit I wasn’t aware existed. One of my favorite places is a small farm stand in Bolinas, near the coast. No cashier, no signage. Just a wooden table, a Venmo code, and natural vegetables still covered in soil. That dirt feels honest.

My husband and I found a small, family-run vineyard in Napa where we held our wedding. They make just a few hundred bottles a year. It wasn’t just about the wine for us, but the sense of belonging that transpired through creation with authenticity.

But even here, a fever of anxiety lurks beneath the surface in our relationship to food. A form of hyperawareness. Food is something to be managed, not something to share; the dining table has become displaced as the hub of the home, and food feels severed from family.

Across the U.S., and increasingly in Europe, labels multiply, traditions thin, and access narrows. Organic becomes luxury. Food becomes performance. We begin to question whether real food is still meant for everyone, but it is.

We can bring the joy of trusted food back into livelihoods. I believe this loss of simplicity is rooted in something deeper: A loss of control over our roots.

When we lose our sense of identity and continuity, of where our food originates, and what it means, we become unanchored. We begin to fear the very thing that once grounded us. We lose the ritual, the rhythm, the connection. And this isn’t just about food. It’s about life.

That simplicity can return.

Not through branding or labelling it. But by making it our default option. I will fight for that kind of eating. For its honesty, its pleasure, and its quiet power.

Kristina Vassileva is a writer on human psychology and modern cultural identities.

Dear Kristina, This is a great essay. It is very heartfelt. I grew up in San Francisco. My wife is European. I really identified with what you wrote. I love a couple sentences, such as: You must transcend the sin of pleasure; dirt feels honest. There are many more great thoughts, too. I look forward to reading more of your thoughts.

I admit to be of the ignorant type, living more on beer than of other stuff. But I liked this. The most joy in eating is when you're really hungry. Or in german: hunger is the best cook/chef.