Say No to the Grind

We need more

Wake up at 1 a.m. in the freezer. Uncomfortable? Good. Drag a tire to work by listening to five self-improvement podcasts at once, fire ants in a diaper to keep you going. Get to work on Chinese keyboards, don’t know Chinese? You will. Broken glass for lunch. Get hit by three cars while driving home and listening to audiobooks at two-times speed. Broken legs? Good. New Record. Roaches kissing you all over, they understand the grind. - Be Jocko, by Wormwood and Countereculture.

The most alarming part about this video isn’t its content. It’s how familiar and recognizable the rhetoric is. Anyone who’s scrolled too long on social media will have seen a clip of a tough-looking man describing daily rituals of self-inflicted suffering as a means to achieve success. That, in short, is the definition of the grind: working hard, against all odds, on your own.

David Goggins, a retired Navy SEAL and one of the best-known proponents of the philosophy says, "It takes relentless self-discipline to schedule suffering into your day, every day.” He’s not alone. Goggins, Jocko, and the rest of the former commandos of the grind vanguard have found an audience. Although not gender-specific, it’s more popular among men, particularly those in their 50s.

But the message is falling increasingly on deaf ears. For many, particularly among younger generations, modern life already feels distinctly like suffering. Scheduling it into your day seems not just unnecessary, but a form of increased submission to a system that is no longer conducive to a life of value.

The grind men “made it”. They came from a challenging background. They’ve been through hell. Yet, they were able to ascend regardless, by working hard, by being disciplined, by refusing to let emotions get the best of them. It didn’t matter if they had a bad day; they still put in the work. Every injustice was endured in silence, alone. Through sheer willpower, they proved that obstacles were temporary, resistance was futile, and the doubters were wrong. Goggings claims it’s how he went from being bullied in school and told he had learning disabilities to becoming the “toughest man in the world”.

But this philosophy isn’t resonating among the millennial and zoomer generations, and there is a reason for it: It doesn’t work for them. They’ve tried it, and haven’t seen the fruits promised by the Gogginses and Jockos of the world. Most now get up early, perform unrewarding work late into the evening for an indifferent conglomerate, and then carry themselves home to a small, empty, mortgaged apartment they may be able to pay back in a few decades. It’s not just that the work is unrewarding; it’s fundamentally discouraging because no tangible fruits can be reaped at the end of this process. If you follow the rules, you won’t necessarily “make it” anymore. Claiming that the fault is yours fails to assess the deeper issues at play.

Many articles are dedicated to how our generation is afflicted by too much comfort. The proponents of toughness argue that an excess of security creates passiveness from an absence brought by adventure. This argument is valid, but not for the reasons they suggest. The baby boomer generation lived a life of relative ease, with a stable, well-paid employment, affordable housing, and the bull markets of their time. Theirs was a utopia that is scarcely imaginable now. We don’t need to descend into a victimhood mindset to observe that what is missing isn’t struggle, but meaning through the suffering.

The grind philosophy primarily derives from a generation that came after the boomers and before ours: Generation X. They rode the wave of baby boomer ease before the impending societal dissolution. This reversal found expression in the grind. They preach to a young generation how to “make it”, because they were only just spared the consequences of the new era of precariousness.

Determination, resilience, and discipline are necessary, but no longer sufficient virtues. The problems that we’re seeking to solve—the atomisation of the individual, cultural and spiritual loss, the capitulation to a depressed economy—are not susceptible to brute force. They can’t be worked away. They are indifferent to personal effort, and require creativity and collaboration to create a new system antithetical to grind culture's individualist quest.

Even if we take the grind philosophy on its own merits, abstracting it from the generational circumstances that led to its rise, it is still found wanting. It is rooted in a combination of stoicism and a work ethic based on discipline. Stoicism is a philosophy predicated on control, though I argued in this article, it represents an unhealthy suppression of our emotions that leads to passiveness. The work ethic philosophy is one of sacrifice to achieve success against the odds. The two combined can create a dangerous mix of passivity while suffering with the illusion of control. Achievement comes not from doing more with less, but making the best of the cards you were dealt with. Feeling like you are constantly suffering is a clear sign that the environment is malfunctioning. This is a law that applies equally to all living organisms.

As a way of being, the grind is fundamentally solipsistic. Reality becomes externalised, something to be stoically endured. All that matters is the self-discipline with which reality is approached. The old ‘live to work or work to live’ dichotomy becomes blurred, the struggle is life. In this sense, the grind becomes what Kierkegaard would describe as the despair of defiance. The defiant self “wants to spite or defy all existence and be himself with it, taking it along in steely resignation with him, almost flying in the face of his agony.” For Kierkegaard, despair constitutes a failure to properly relate to oneself.

Enduring challenges for a greater purpose is fundamentally distinct from deliberately creating suffering, as an end in itself, to stress yourself and touch the limits of your tolerance. The “grind” shouldn’t be a life of intentional pain but about finding the beauty in it. That can only be realized through a lens where suffering is not the objective, but a necessary consequence of meaningful change. Nietzsche distills this down to the axiom, “He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.” In inverting this principle, the grind mentality shows its limitations, sacrificing the richer ‘why’ at the altar of a dubious ‘how’.

Grinding is also a self-referential philosophy: “I promote this lifestyle because I became noteworthy for promoting this lifestyle.” If we observe individuals who achieved greatness by breaking down barriers and creating something larger than themselves, we can observe a different dynamic at play. This philosophy is prevalent with men of military background, but not so much among pioneers and leaders. Even if we look at combat sport icons, who are supposedly grind disciples, the reality is that they live a life of “dysfunctional functionality” to turn their dreams into a reality. They rely not just on effort but on the power of instinct, which is antithetical to control.

In an interview, the UFC champion Conor McGregor spoke of the fact that he was never an early riser, that he trained in combat sports until late at night but that you “wouldn’t catch me in the morning”. Maybe if he had forced himself to be “functional” and wake up at 5am, as advocated by the grind philosophers, he wouldn’t have become a UFC champion, because excellence requires a degree of listening to our unique needs. That doesn’t mean indulgence; it means observance of the dysfunction that sometimes can make us function better. Likewise, Jon Jones, widely considered the greatest MMA fighter of all time, claims that he would deliberately be dysfunctional before a fight to make sure he showed up relaxed and unprepared. “I had this crazy thing I would do where I would party a week before every fight, my logic was, if this guy were to beat me, I would look at myself in the mirror and think, ‘Well I lost because I got hammered before the fight.’” He said, “When I didn’t do that, I had my worst performance.” By not training to the best of his ability before a fight, he would not be forced to face the possibility that he could be beaten at his best. It was not necessarily a “healthy” belief system, certainly not one consistent with the grind mentality, but it allowed him to enter a flow state that made him undefeatable. These men train, suffer, fight, they fail and they work hard to get back to the top, stronger than before. But they do so with a vision, and they practice discipline with a form of surrender to their instinct in order to create it, and, more crucially, to let the vision create itself.

This is especially true for those working with creativity and invention. Efficiency and optimization come at the price of genius and quality. Sometimes, descending into the abyss and letting it swallow you up allows you to find new ideas there, better ones than before. To realize where you could improve. Grinding doesn’t leave you that room to pause, because you become akin to a drone machine that never stops charging. Quality fails under these circumstances, because sometimes, you need to hit rock bottom to resurface. It’s not about quitting, because that would mean never coming back. It’s about embracing the cycle, reflecting on its lessons, and recommitting to yourself.

Leonardo Da Vinci took 14 years to complete the Mona Lisa, he was busy otherwise with other projects he never finished, brainstorming on human anatomy and airplanes, for the sake of learning and nothing else. He was financed by patrons who trusted in him, allowing him to live this lifestyle without worrying about financial repercussions. He said, “Men of lofty genius sometimes accomplish the most when they work the least, for their minds are occupied with their ideas and the perfection of their conceptions, to which they afterwards give form.” What would we have made of him today, with market demands forcing him to grind?

I’m a writer and a painter. While I require a base level of stability around me to function, I wrote my best pieces late at night, engulfed by the silence and darkness that allowed me to focus. Sometimes, I need to pause for hours, to distract myself and come back with new eyes. “Creative people need time to sit around and do nothing,” said the author Austin Kleon. In our efficiency-oriented society, these words appear as a form of idleness, because we’ve become accustomed to a mindset based on strict productivity. But my best paintings weren’t the ones I made when I was forcing myself to reach perfection or struggling to respect a deadline. Those were my worst paintings. My best paintings came when I was somewhere between discipline and surrender. That feeling of meditation that derives from being so immersed in a practice you forget outside reality exists. It feels, not like a grind, but effortless.

Rigid routines, in this context, can inhibit potential. Though structure is necessary as a point of reference, sometimes we need to trust ourselves to bend it. That’s how intention and dedication meet spontaneity and momentum. Some work better under pressure, I’m certainly one of them. But there’s a kind of pressure that allows your mind to act instinctively, to reach the height of its potential. It provides an exciting challenge. The grind is about forcing gruesome pressure you don’t need consistently, and instead of rising to an occasion, we end up feeling drained by exhaustion: the occasion doesn’t show up.

Grinding is based on rigidity, the idea that we have to keep going, no matter what. That we have to reach the best result, always, in a stable, formulaic manner. But that can lead to neuroticism. If an elements falls out of place, unpredictability under this maximized routine can cause the system to fall under its own weight. Giving our best involves working through ups and downs, and learning to ride each wave as it comes. Being flexible means that we are alive. We can adapt according to what we face. Only inanimate objects are inflexible, and those don’t achieve much.

Life today is challenging enough as it is. Not because we’re overloaded with comfort, but because challenge is presented under the guise of comfort. The disconnection brought to us by social media, the inflation brought to us by printing more money, and the chaos by a political system that claims to listen to our needs. It leads us to feel increasingly frustrated. We’re not fighting wars in the trenches like our grandparents, but we’re fighting much more subtle, insidious battles, against an enemy that tells us to grind away the last sparks of energy and inspiration we have left. We must, instead, rebel against it. The virtue of courage today is the rarest, and the most needed.

It’s a grind to resist the temptations on the internet. It’s a grind to wake up every morning without the promise of a better future ahead of you. It’s a grind to keep working despite not seeing the results your parents enjoyed without an ounce of your effort. It’s a grind to endure the loneliness of a pandemic lockdown, to survive an economy working against you, to witness rising crime at home and the threat of a war on the horizon, to feel uncertain about every moment.

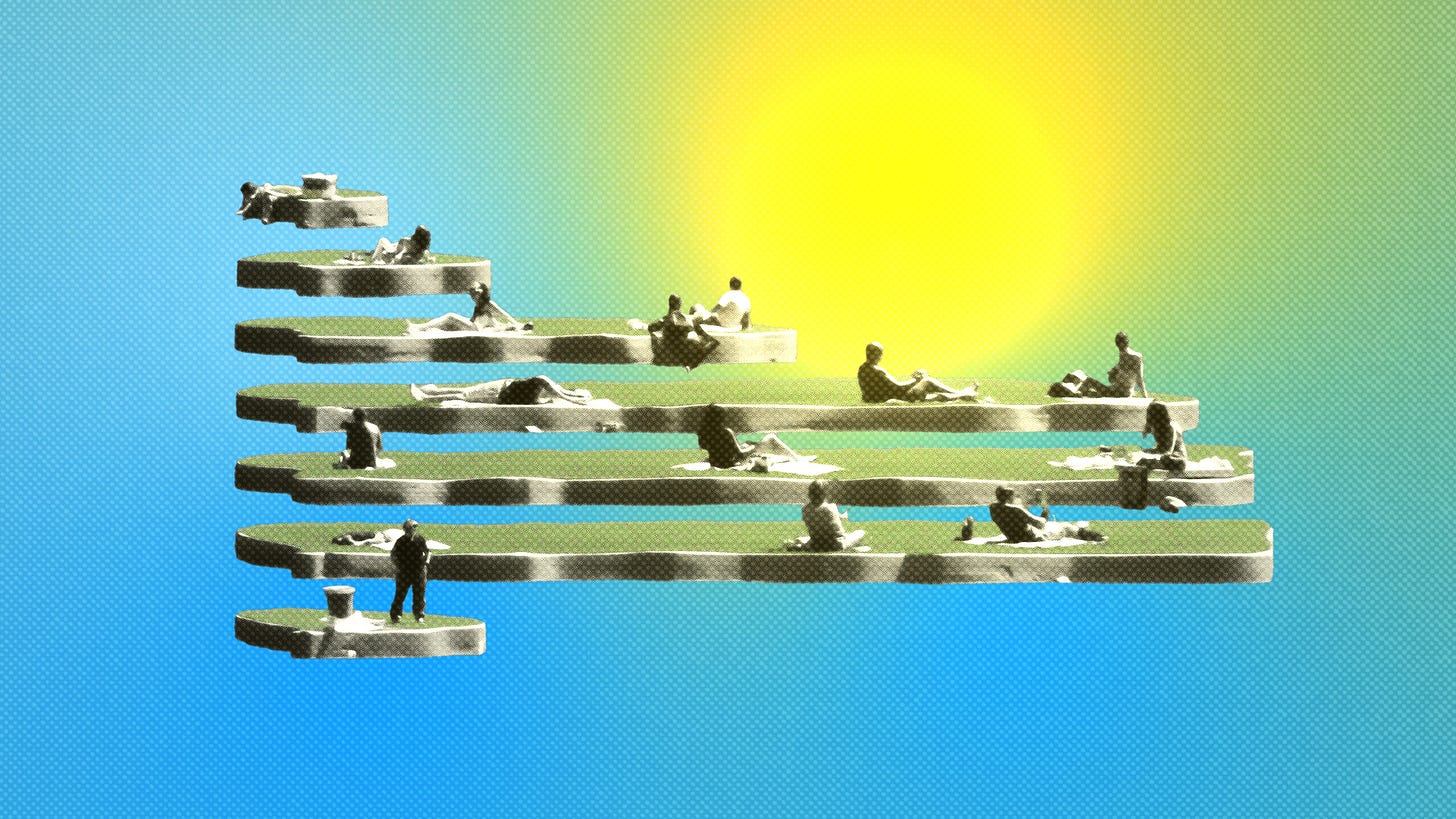

We don’t need more grind; we need less. We need to find joy through meaning and lightness through instinct. We need to feel the adrenaline of excitement running through our veins. That’s when we gladly carry the suffering that may come with it.

Alessandra Bocchi is the founder of Alata Magazine and Rivista Alata.

Beautifully expressed. My work in the realm of sculpture has shown me how more primitive, less ‘optimized’ tools are often the most conducive to creativity, flow, and skill development. The grind is so antithetical to art-making, and I worry that our social and economic trends will eventually abandon any arts that require capital and overhead to practice.

It’s also a pleasure to see the word ‘invention’ applied here - I’ve been musing lately about what it means that we’ve largely abandoned the word in favour of ‘innovation’. We’ve given up on the idea that there’s anything left to discover, and that contributes to the pervasive sense of meaninglessness.

I was about to close the window thinking this would be yet another Millennial we-got-screwed screed (Yes, I'm a Millennial). I'm glad I didn't.

I still think that Millennials overstate the dysfunctional state of society and the good fortunes previous generations, but the latter half of this essay is excellent.