The New Golden Age in Art

We need the beating pulse of self-love

While many nostalgic commentators lament the loss of Western art, few are willing to define its values or trace its origins. To better understand what defines our artistic heritage and how we can think about a new future for it, let us first contrast it with the art of the Islamic world, a culture that is radically different and yet so close to Europe.

Western art primarily depicts the human body, often naked, and the objects surrounding it in figurative form, with statues, drawings, and paintings, including in our Churches. However, Islamic art largely lacks any such bodily or worldly representations.

Art in the Islamic world is largely characterized by mathematical and geometrical features. It tends towards the abstract and resembles a “psychedelic” vision; it captivates the viewer through obsessive perfection with detail, symmetry, and warm and vivacious colors. Its creation is deeply rooted in spiritual belief. Islam is riddled with taboos against representing images of the male and female form, or objects around us, as “worldly” and, therefore, impure. According to the Islamic faith, creating an image of the prophet Mohammed would do injustice to him, so their creativity is channeled away from the body and the reality surrounding it.

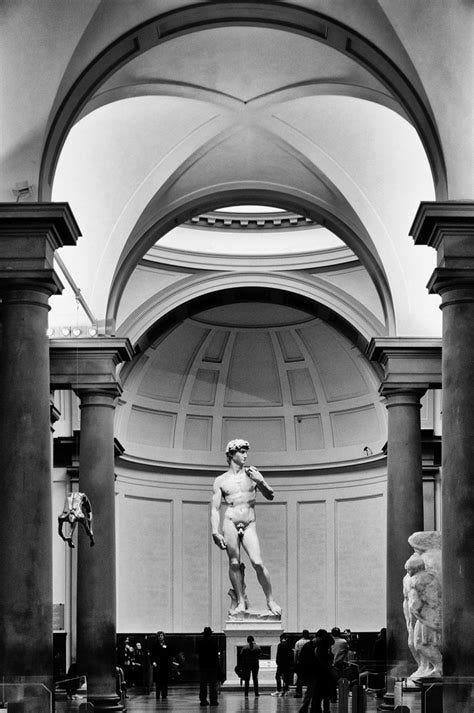

Europeans, instead, are enamored with the splendor of the human form. The Renaissance evokes the allure of the Mona Lisa’s enigmatic features, crafted by Leonardo Da Vinci to enchant with the mysterious nature of human emotions, or the nude sculpture of David, created by Michelangelo to embody an ideal of the male physique, standing tall and gazing over us with a powerful, mighty stare.

The two central Golden Ages that blessed the European continent with striking art took place in Athens in 500 BC and the Renaissance in 1500 AD. In its vast complexity, the elevation of the human form defined both periods. If one takes a moment to notice, a remarkable shift in perception takes place within these works.

The first two are from 600 BC Greece, the century before the Golden Age. They are known as Kouroi statues, “κοῦροι”, characterized by an anonymous, detached, and frosty glare. While they possess a captivating, severe energy, they lack vitality and personality. The feeling they evoke is a representation, rather than an expression, of what is human; they're not alive. In their time, κοῦροι were known as symbols of youth. To the modern eye, they have a cartoonish appearance.

But around 500 BC, a noticeable shift occurred in our civilizational psyche; Greek statues developed richer expressions, nearly perfect realistic form, and a feeling that they were “real.” The statues themselves became alive. They brought the individual to life with them. They held presence.

This change was part of a radical transformation of the culture in ancient Athens: the arrival of theatre, the creation of drama, the grand Dionysian art festival, the athletic competitions of the Olympics, and the rise of Philosophy—our first European Golden Age.

Greek civilization from 500 BC onwards forged the Western spirit as we know it. Mankind broke through to a superior dimension. Its foundations were set in stone as first principles.

Friedrich Nietzsche defended the value of these Golden Ages. He spent his life theorizing how such moments took place and how we could return to the mindset that brought about their creation. In The Birth of Tragedy, he explored the Greek fusion between the opposing Apollonian and Dionysian elements, a balance between order and passion.

During the Renaissance, we can observe a return to classical principles that led to the rebirth of the figurative form of the Greek Golden Age.

After the fall of Rome, Europe experienced a profound alteration. The millennia-long “dark” ages saw the development of a new Germanic cultural center, which the German historian Oswald Spengler defined as the beginning of the Faustian spirit in Northern Europe with Gothic art, while the sun set on the Golden Age of the Classical Greeks and Romans. Medieval paintings from this era represented figures from Biblical scriptures to venerate the divine, but their figures were flat and austere, and they depicted cold, expressionless stares.

After the fall of Constantinople, the classical works made their way through the widening cracks in Christian dogma. The city-states that are now part of Italy witnessed a rebirth of the tragic age—one can see this post-Renaissance even more clearly with the rise of Baroque art. Caravaggio brought theatrical emotions to the artistic arena. Here are two examples of The Mother Mary and Christ from the Renaissance and the Medieval times. One can see how much the figures had gained depth and dimension compared to the flat, one-dimensional ones of the Middle Ages.

The Renaissance brought similar shockwaves to wider society as the Greek ages of tragedy. It was not just a change in art but a profound paradigmatic shift in philosophy, science, and medicine.

The way these fields were examined embodied the nature of their artistic influence. Through Da Vinci’s notes, one will find anatomical diagrams that laid the foundation of modern medicine. He did so directly by digging up bodies and dissecting their parts, a practice that was allowed during the Renaissance after its prohibition in the Middle Ages from the Catholic Church.

Even in the abstract realm of philosophy, deliberations were made about humanism. Phrases such as “man is the measure of all things,” first coined by the ancient Greek philosopher Protagoras made a conceptual comeback. Man became the focal point of study once again, but within a Catholic framework. The human body was understood as the perfect creation of God, and was to be celebrated as such. Through this focus on the human form, the Renaissance set the stage for the earthly study of the empirical world.

But there was a counter-cultural reaction to the birth of a new Catholic, humanist “high culture”. The rising Protestant movement in Northern Europe halted its development. The Reformation was a rebellion, among other perceived sins, against the Pagan origins of Renaissance culture, considered a corruption of Biblical teachings.

Martin Luther believed that art shouldn’t distract from the message in scripture. He rejected the more ornate religious practices of the Catholic Church. Protestant churches are simpler and sober-looking precisely because no centralized, wealthy institution funded their artistic works, and their focus was on upholding the written word rather than exploring the world of imagery.

In this sense, there are similarities between the Protestant Revolution and Islamic approaches to art. The obsession with images of mankind distracts and corrupts the word in sacred scriptures. The iconoclastic fury of Protestants was particularly evident with Calvinists when some of its adherents engaged in violent acts of vandalism against Renaissance, Catholic churches. They destroyed religious art and defaced figures in paintings and sculptures. In some instances, Protestants wrote over religious art with verses from the Bible as they viewed the imagery as heretical. In this way, they resemble the behavior of Salafists who seek to destroy pre-Islamic heritages in the Middle East. The word is at war with the image.

In fact, this counter-revolution appears both times in history against this embodied high culture of the Golden Ages, first, with the beginning of the Christian takeover of Pagan Europe and, later, with the Reformation’s reaction against rising Catholic humanism. Abrahamic faiths, which are religions based on scripture at their core, contain reactionary elements against the world of representational imagery when taken literally. The Catholic Church was the only exception during the Renaissance as it was the most Pagan of the Abrahamic faiths, a remnant of ancient Rome's institutions.

Nietzsche noted that as the Greek Golden Age was ending, we witnessed the rise of Socrates. The philosopher of reason, as depicted by Plato, began to question accepted beliefs. Plato proposes that art and music should be regulated based on what is in the interest of the public good, introducing the first forms of censorship.

When the Christians rose in Rome, they replaced Europe’s polytheistic faiths with monotheism, which only accepted one God; a concept that originates in Judaism. They claimed Pagan representations of the divine were false, demonic idols. They defaced the genitals, faces, and noses of ancient statues. Christianity experienced a crisis of conscience with Europe’s representational art. The instincts of the Romans wanted to explore the human form, but the question “Is this idol worship?” echoed in their newly founded Christian beliefs. The Renaissance attempted to merge these two worlds into one.

To this day, this contrast causes tension and confusion on the identity of the Western soul. The psychology of scripture pulls us toward the austere cleanliness of religious piousness, discipline, and order, but the explosive psychology of the body, of the Pagan Gods and Goddesses that were representations of higher human forms, launches us toward lust, majesty, and glorification. Our history ebbs and flows between these forces.

I’m not a bearer of good news for our age. But I do believe we have the potential to overcome it. We could experience a new Renaissance. We’re close to it, but we’re not there yet. We’re more akin to the rigid Medieval cartoons, the strict Islamic restrictions to artistic expression, and the Protestant obsession against profanity.

The brutalist architecture surrounding us since the end of the Great Wars feels domineering, and the Artificial Intelligence generating billions of representations of art evokes a cold, machine-like presence that lacks the passion and emotion of true art because humans themselves did not make it.

But even handmade attempts at creating art today lack the mysticism of our great masters. Michelangelo said he was “freeing an angel trapped in stone” when carving his sculptures. Can we look to a figurative sculptor today who can do the same without falling into the plastic culture of the hype men of the Silicon Age? They laud how some artists craft modern statues like the one below and announce that the West is in Renaissance 2.0.

These works lack the forceful, living presence of true art. The skills required to make them are technically impressive, but they embody the lifeless stare of early Greek statues, Medieval cartoons, or what Midjourney generates daily. They lack an ethereal nature, simply emulating the commodification of bodies we see in modern-day Instagram models. They are, as yet, merely attempts at mimicking high art.

Of course, our rigid and lifeless era is born out of a sense of confusion about who we are in the West. We’ve been taught self-hatred and shame since the end of World War II. Perhaps some of us feel that we need to pay for our historical sins, but we cannot respect and castigate ourselves at the same time. The Golden Age comes with the beating pulse of self-love. To glorify your body, you must first love it.

As we create a path towards a new Renaissance, we need to revolutionize our understanding of who we are. That begins with remembering the spirit of our Golden Ages. After all, a great remembering drove the first rebirth. Let us remember once again.

Stephen Plunkett, known under the name Uberboyo, is an Irish writer and YouTuber.

I work with a contemporary figurative sculptor who eschews the "plastic culture". You might like his work. www.robinsonstudio.com

This is a very well-written article. It sounds like a fundamental premise of the piece is that the recognition of the divine in man is an essential precondition to creating art that embodies this divine dynamism and beauty. Would you say that beautiful art is, then, predicated on the right understanding of the relation between man and God? Are we, then, overdue for a spiritual rebirth? Or are you hopeful that a new Renaissance can emerge in a secular age? The movements which sought to dwarf man's value in relation to the divine, such as Islam and the Christian iconoclasts, producer lackluster art, after all. It seems like if there isn't some divine measure by which to judge man and strive towards, then we will lack the motivation to elevate our art and man himself to any such beautiful ideal. Humanism without the recognition of the divine seems to devolve into authentic depictions of ugliness, such as how the Romans gradually deviated from the Greeks by depicting the candid forms of their emperors, imperfections and all.