What Happened to Twitter?

Why I deactivated my account

I deactivated my X account despite the fact that I had my largest following on that account alone. It’s worth explaining why, because it might make a difference, and because there’s a deeper lesson to learn from it. One we can trace back to mythology.

Whatever your interests were, but especially if you were engaged politically, Twitter as a social media platform uniquely made you feel like you were part of a mission larger than yourself. Unlike other platforms, it offered the opportunity to share your ideas in writing and have others directly engage with or critique them. That’s what made Twitter both toxic (because of the constant verbal conflict) and noble (because of the aspiration for a higher purpose).

That sense of visionary comradeship was gradually lost once Elon Musk purchased Twitter, turned it into X, and started rewarding fast entertainment at the expense of substantive thought. Opting for posting some photos here and there with a “GM” caption felt simpler than my previous analytical posts that required research, until I grew tired of the spectacle: I cut off the bull’s head and deactivated my account entirely. I felt no resistance; it wasn’t a New Year’s resolution intended to control screen time or addiction to social media. It felt swift and easy, and I feel cleansed because of it. A clean breakup.

With the rise of AI, many of us feel more cautious about posting ourselves online. As Grok started undressing women, there was a sense of violation of our dignity that rightfully caused an uproar. That was the last straw for me. I wasn’t excited to log on to see who was saying what; I didn’t feel like sharing my ideas there anymore. Not because I didn’t feel passionately about them. I feel more passionate now than I ever did. But because the Twitter I once loved has become something I no longer recognize.

It’s not worth ruminating on the past. That’s why I deactivated. “Bye Felicia” is more often than not the mantra we need when something we tried to make work stops working for us. But when we become so accustomed to a change, we forget how things were before that change took place. It’s worth remembering the past to track whether there has been progress and to see if there are lessons to learn.

Twitter is where I started out sharing my work as a journalist. I barely used social media before that; it represented an alien world to me.

That quickly changed when, at the age of 22, I aspired to become a journalist rather than pursue a PhD in Philosophy. I was told I needed to create a Twitter account, so I did. But I barely used it - I had 200 followers. Yet, my career took off as a journalist, quite randomly, thanks to Twitter.

I was DM’d by two Vice journalists when I argued and had quite an aggressive fight on the platform with an unhinged British jihadist apologist who was threatening to ruin my life. This man had one hundred times my follower count and far more traction. Because I felt cornered, I went for the jugular and told that man to stop attacking me, and exposed him for being a propaganda mouthpiece for TRT - the Turkish State Television Network. When the Vice journalists messaged me in private to show their support for my response to him, I looked up their names and realized they were “famous”, while I was struggling to get myself and other employees paid by the newspaper I was working for, which could barely stay afloat. It made me feel more protected, like I wasn’t alone. This was while I was working my first job in journalism in the Arab world at 23, by myself, so I didn’t feel as safe given the ideas I was espousing at the time against the Islamic takeover of Europe.

Why do I mention this? Because a young journalist like myself with 200 followers who barely held a job could rise through the ranks by simply being bold and having something of substance to say. It was a time when these virtues still mattered. That’s no longer true. I enjoyed Twitter because we could share our most intricate thoughts, and you could see compelling debates unfold in real time with pretty much anyone, including heads of state.

Twitter was a realm of unfiltered ideas for us as dissidents, where we could speak freely of the most taboo topics affecting us, before the censorship began. We were fighting an uphill battle: The regulators and the mainstream blue checks were opposed to us. But this made the fight all the more invigorating because you had the opportunity to stand out. I was invited to the first events, interviews, TV shows, documentaries, magazines, newspapers, podcasts... All through Twitter. I was always camera-shy, part of it was self-consciousness, part of it was not wanting to be rewarded or picked apart for my looks, but to be valued for the quality of my work, despite the many offers to fit the “pipeline” of trad-journalist girls - creating viral media content with the fandom of right-wing men. That was going to be an easier path to fame. But I was too prideful and perhaps too vain to go down that road. So I remained a journalist who wrote, rather than one who appeared, and Twitter allowed me to do just that when other platforms rewarded image and video content only. There were editors for magazines and newspapers who reached out to me. I was used to sending my story pitches into the abyss; suddenly, I was being asked to write thanks to the exposure Twitter afforded me.

I met the most interesting and exceptional people. It was a space where you could connect with like-minded individuals through the virtual world, to the point that connections in real life that didn’t share that ideological affinity felt less authentic. Strong counter or subcultures were created through this platform alone.

To make it on Twitter, you had to have something original to say, and you needed to be fearless about your views, while still walking a thin line to avoid being banned. There were standards, however much we disagreed with them.

But what was formerly Twitter has now become a place without standards at all, one for artificial slop and an echo chamber of nihilistic irony. To give credit where it is due, Elon held a noble vision for purchasing the platform. He sought to remove the censorship and compensate creators monetarily through engagement. But as the proverb goes, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. The opposite took place. Now we have endless brain-dead AI videos with the usual community note disclaimer, “This video is AI”, engagement rewards the most inane posts, feeds are congested with an algorithm that promotes whatever is most popular, instead of what we intentionally decide to follow, and what adds value to our lives and our understanding of the reality we inhabit.

The concept of algorithmic rewards is also fairly recent, and it doesn’t make much sense. Clicking on one post does not, in any way, mean that it is your sole interest and that you should see a million versions of the same subject. The algorithm stripped us of our sense of autonomy and intentionality. We could once decide for ourselves what to see, and we were exposed to what we didn’t like, too. We could learn and grow from that exposure, but that exposure was controlled; it wasn’t forced on us. Now, many of us find ourselves waging a war against an algorithm that tries to impose what becomes viral or what we may have clicked once out of idleness. We have to mute certain words or go on a tirade of blocking certain accounts. The machine appeals to our lowest impulse, rather than our highest virtue. But is this a war worth fighting? Many, like myself, have realized it isn’t.

The fall of Twitter follows that natural cycle of life, and there is no need to be nostalgic about it. Empires rise and fall, and so do companies. To keep up with the pace of change, you need to adapt, but not outgrow. Elon is a brilliant innovator in the field of mechanical engineering. But placing a man with autistic tendencies and a very optimized outlook on life in charge of our social interactions online wasn’t the wisest idea. He was not fit to lead a giant communication-based company like Twitter because his understanding of human emotions or relationships is more limited. That doesn’t mean he’s less of a genius because of it; it just means he was out of his depth in this particular circumstance. He could have bought the platform and chosen a trusted advisor to manage the major decisions to fulfill his vision.

The first signal of Twitter’s decline was changing the name from Twitter to X. The bluebird, meant to portray birds chatting, represented by the onomatopoeia of a “Tweet” (the sound birds make when they speak), was endearing. Then Elon decided to replace it with an anonymous, alienating black X, which resembled the slogan of a dystopian technocracy. Images matter.

The second mistake was removing blue checks as a hierarchical system based on status and making them about a payment. Elon intended to democratize the system and remove a snobbish attitude that liberal, establishment “experts” with blue checks had over the rest of the masses. But status is not supposed to be a commercial exchange that you can buy your way into, like purchasing a t-shirt, or it loses its value. I agree, the previous blue checks were annoyingly condescending, and a new system was needed. But I was required to earn my blue check by winning a prize at the WSJ. I’m not saying that’s the standard we should aspire towards. But you need a standard, or you risk falling into relativism.

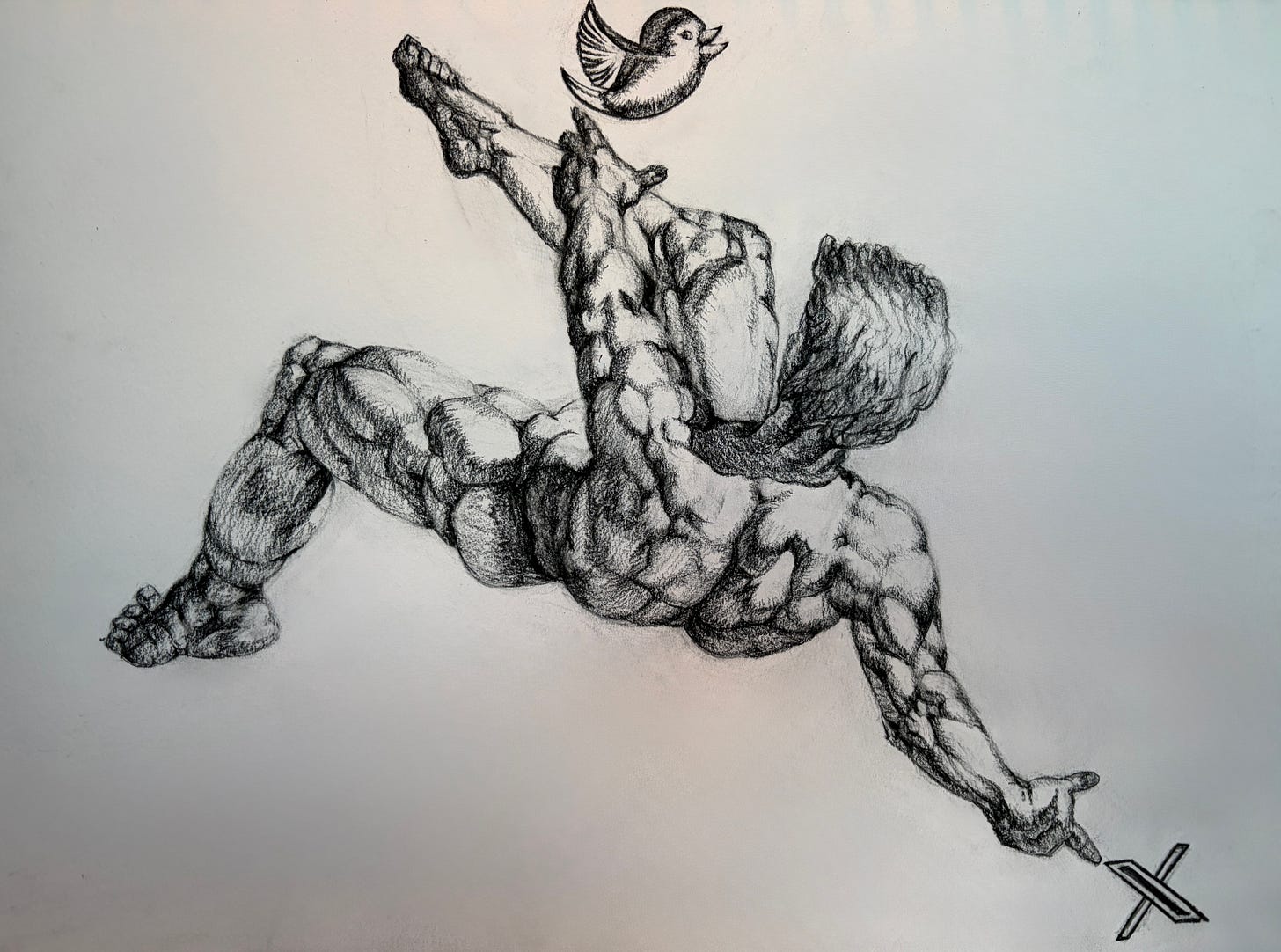

The third mistake was making it the “everything app”. There’s an Italian proverb, “Chi troppo vuole, nulla stringe.” It means, “Those who want too much, achieve nothing.” Like the Greek myth of Icarus, who flew too close to the sun, Elon’s vision was so ambitious that it turned into hubris. Elon should be appreciated nonetheless for his intention to create a project that would allow us to become free to express ourselves. It just so happens that when you aspire for too much, you end up falling with your face flat on the ground. That didn’t happen to Elon, but to X. Achievement requires a degree of humility, not just ambition. The following quote was attributed to Oscar Wilde, the Irish poet and author:

Never regret they fall, Icarus of the fearless flight, for the greatest tragedy of them all, is never to feel the burning light.

He’s right, because without risk, there is no chance of success. However, we can also learn from Icarus about the importance of level-headedness. Let’s not be too hard on Elon, but let’s be hard enough that he’s required to make adjustments based on the admission that his goal hasn’t borne the fruits he hoped for. Not necessarily by returning the platform to what it once was, but by using the greatness of its past as a blueprint and adapting it to the needs and tools of today.

Substack now seems like the only place where we can find quality again - thoughts and individuals of substance. Though it’s missing the punchiness and the cutting debate of the previous Twitter, it’s a space where you can read about the ideas of our time in a calmer, denser essay format. It’s different, but it’s good.

I’m done with X - because I loved Twitter. I may return to promote these essays on Substack, but I still won’t enjoy it as much as I once did. I hope Elon can restore the talking, often hysterical but lively birds from the hellish AI slop and the banality of content it has become.

He certainly still has the power to recover from Icarus’ fall.

Alessandra Bocchi is the founder of Alata Magazine and Rivista Alata.

Welcome back Alata-

Thanks for sharing why you left, which I noticed recently. I’ll miss your thoughtful posts. I agree that the platform has changed (it always required filtering, but it requires much more aggressive filtering than it used to). I hope this frees you up for both your journalistic and artistic ambitions!